Injury

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a ligament located inside the knee and responsible for providing stability to the knee with rotational movements or twisting. For a complete discussion on injury to this ligament, see our blog article (https://adamanzmd.com/acl-knee-injuries/). While ACL surgery is most often successful, there are occasions where reinjury can occur. In some instances, reinjury may involve a tear of a previous ACL reconstruction or repair.

When looking at reinjury rates in the general population, one study found a 4.2% rate of revision reconstruction at 5 years1 and that patients who were young at the time of the reconstruction were more at risk of reinjury. Another study in patients under 20 years of age who had an ACL reconstruction found that 18% reinjured either their reconstructed knee or their other knee2. Of reinjuries, 90% occurred during high-risk sports.3 A systematic review comparing autograft and allograft reconstructions in young patients found a higher reinjury rate in patients under the age of 25 who had an allograft. (9% and 25%, respectively).4 It is clear that reconstructions involving younger patients are more at risk of reinjury, and allografts in young patients are at a higher risk of reinjury.

Symptoms

When an individual retears their ACL, there may be less pain and swelling then when they injured their knee the first time. Patients typically report similar feelings of instability than what they felt prior to their first surgery. In some instances, they may sustain a meniscus tear at the time of their reinjury, and the knee may be locked from full extension (straightening). In younger, active patients a revision ACL reconstruction surgery is often recommended.

It is hard to know for certain why a re injury occurs. Some reasons may include: a too soon return to cutting/pivoting activities, too little rehabilitation, or new trauma to the knee (such as a fall or impact to the knee during sporting activity). Once a re-tear occurs, the knee is likely unstable and must be carefully addressed to restore function to the knee.

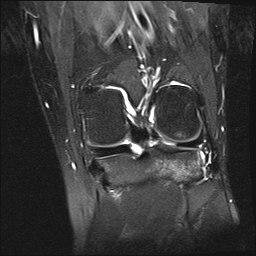

Diagnosis

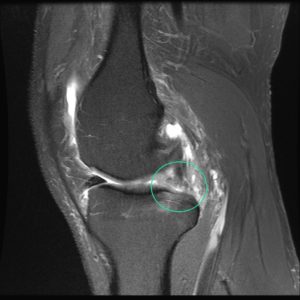

Dr. Anz will assess the knee carefully and will order new X-rays and most likely an MRI. New X-rays and MRI help to fully understand the extent of, possible reasons/risks for, and the best steps to take to address the reinjury. In some instances, a CT scan helps to see the status of femur and tibia bones, considering the previous bone tunnels/sockets used during the first surgery.

Treatment

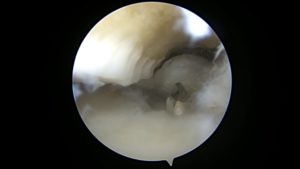

An ACL revision surgery may be the best way to return athletes to the level of sport which they seek. Revision surgery is more difficult to perform because previous devices used with the first ACL surgery and the tunnels created for the first surgery affect the revision surgery. In certain cases, a revision ACL reconstruction can be performed immediately, in one stage. In other cases where the previous bone tunnels create hurdles, a revision surgery in two stages may be the best course of action. In two-staged revisions, a bone grafting surgery to fill the areas with new bone is the first stage, and a second-stage surgery , 3-6 months after the first stage, to place the new ACL reconstruction graft follows.

Post-Operative

Patients will be prescribed a clear and thorough rehabilitation program following revision ACL surgery. After surgery patients will be placed into a brace and will typically use crutches for 2 weeks. Rehabilitation will be a progressive process that may initially limit movement. The first phase focuses on swelling and the return of normal knee motion. Further phases focus on regaining strength, balance, and functional movement patterns.

Recovery Time

After a first ACL reconstruction, cutting and pivoting activities are limited until around the 7 month time point as graft maturation takes time. With revision reconstructions, this may be pushed to the 9 month time point. Two studies on reinjury rates suggest that risk decreases significantly with every month until the 9-month time point. For this reason, in most instances a return to cutting/pivoting sports is cautioned before the 9-month milestone.5 However, every athlete is unique and situations are unique. Some instances dictate a sooner return to sport than 9-months understanding the risk. Post-operative rehabilitation and returning to sport is a joint effort/decision between the patient, Dr. Anz, the physical therapist, and the athletic trainer and is necessary to achieve the most optimal outcome.

Athletes with ACL injuries should not feel bad if it takes time to return to their sport. In many instances it takes athletes one to two years to make a full return. A study in high-school and college football players found a return to sport rate of 32% at one year and 64% at two years. 53% of high school players and 50% of collegiate players identified fear as a major or contributing factor to not returning to play sooner.6 Dr. Anz and his team serve as advocates to help athletes return safely and expeditiously to their sport, considering and helping with all hurdles along the way.

For additional information on revision ACL reconstruction surgery, or to learn more about common knee injuries involving one or more ligaments within the knee, please contact the Gulf Breeze, Florida orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Adam Anz located at the Andrews Institute.

Sources:

- PubMed.gov, Authors: Andreas Persson, Knut Fjeldsgaard, Jan-Erik Gjertsen, Asle B Kjellsen, Lars Engebretsen, Randi M Hole, Jonas M Fevang. Date: Dec 9, 2013. Link.

- PubMed.gov, Authors: Sue Barber-Westin, Frank R Noyes. Date: May 6, 2020. Link.

- PubMed.gov, Authors: Hideaki Fukuda, Takahiro Ogura, Shigehiro Asai, Toru Omodani, Tatsuya Takahashi, Ichiro Yamaura, Hiroki Sakai, Chikara Saito, Akihiro Tsuchiya, Kenji Takahashi. Date: Dec 9, 2013. Link.

- PubMed.gov, Authors: David Wasserstein, Ujash Sheth, Alison Cabrera, Kurt P Spindler. Date: May 7, 2015. Link.

- PubMed.gov, Authors:

Susanne Beischer, PT, PhD, Linnéa Gustavsson, Eric Hamrin Senorski, PT, PhD, Jón Karlsson, MD, PhD, Christoffer Thomeé, BS, Kristian Samuelsson, MD, PhD, Roland Thomeé, PT, PhD. Date: Jan 31, 2020. Link. - PubMed.gov, Authors: Kirk A McCullough, Kevin D Phelps, Kurt P Spindler, Matthew J Matava, Warren R Dunn, Richard D Parker, MOON Group; Emily K Reinke. Aug 24, 2012. Link.