Returning to Sport Following ACL Reconstruction

After ACL reconstruction1, the most common question is also the most difficult to answer: “When will I be ready to go back to ___?” In short, there is no blanket answer; there are many factors that determine when the time is right for a patient to return to sport. These factors are physical, biologic, and psychological in nature and they affect each patient’s recovery in a unique way. At the end of the day, returning to sport is a decision that needs to be made on a patient-to-patient basis, weighing the benefits of continued rest and rehabilitation with the risks and benefits of returning to sport.

How and When Do Most Athletes Return

It is helpful to consider the track record of other athletes’ road to recovery following ACL reconstruction. Traditional wisdom holds that athletes return to sport within 6-12 months of an ACL injury. However, recent studies have turned this idea on its head. One study evaluated 187 amateur and competitive athletes with ACL injuries and found that only 31% returned to the sport in the first 12 months, and that number only climbed to 60% at 24-months post-surgery.2 Another multicenter study examined the question with a specific focus on football. Researchers contacted 147 high school and collegiate football players and found similar return-to-play rates in both groups two years post-surgery—63% and 69%, respectively. However, only 43% of the players interviewed believed they returned to previous self-reported levels of performance; 27% felt that they never reached their pre-surgery performance and 30% were unable to return at all. Surprisingly, fear of re-injury or further damage to the knee was cited as the most common reason that players did not return to play.3 This study highlights two important facts: 1) return-to-play rates for football players are not as high as one might expect, and 2) psychological factors, particularly fear of re-injury, play a key role in athletes’ return to sport.

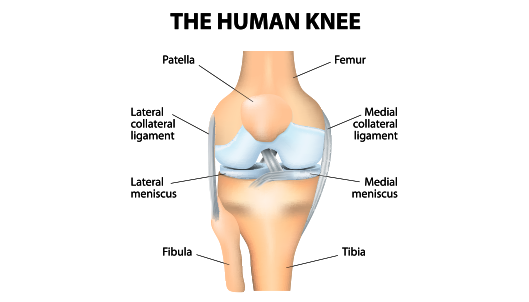

Physical Therapy: Motion, Muscle Strength, and Proprioception

Physical therapy following surgery is just as, if not more, important than the surgery itself. After most ACL reconstructions, full restoration of range of motion in the knee is the first goal of therapy, except in cases involving complex meniscus repairs. Once motion is restored, strength becomes the next goal. During this phase, athletes may find that it takes longer than expected to recover pre-injury strength and mass in the muscles surrounding the knee. This can be frustrating, and it is surprising how different patients recover at different rates. The key during the strengthening phase is to work hard and be patient. While strengthening the muscles, therapists will also help restore normal/athletic proprioception and functional movement patterns. At this point, it is common for athletes to not experience pain, yet still have significant strength and coordination deficits.

A physical therapist is your most important resource during rehabilitation. They have the experience and skills necessary to help athletes realize where they are in the process, set appropriate goals, and find a balance between activity and rest—both of which are critical to recovery. The athlete, their family, their therapist, athletic trainers, and the physician are all part of a team working together during the recovery process. This process takes time—anywhere from 6 to 24 months—and can vary due to the extent of injury, the athlete’s stage of life/career, and how quickly one’s body recovers. The key is to be patient and persistent, allowing the entire team to help guide the process.

“No Doubt”- The Return of the Confident, Athletic Mindset

Confidence and risk are the final factors that must be considered as an athlete prepares to return to sport. As highlighted earlier, 50% of athletes cite fear of reinjury as the primary obstacle to returning to competition. There are two potential explanations for this fear: 1) a graft that “just doesn’t feel right” may not have completed the ligamentization process, or 2) traditional rehabilitation does not focus on the athlete’s competitive mindset.

While research seeks to eliminate the first cause—and our next blog will address these efforts in detail—only a team-based approach, consisting of the athlete and their family, the physical therapist, athletic trainers, and physician can resolve the second. Close communication is important to understand risks and expectations, set and achieve rehabilitation goals, and confirm the return of normal function and strength. While it is ultimately up to the athlete and their family to decide when he or she is prepared to return to full competition, at the Andrews Institute in Gulf Breeze, Florida, Dr. Anz, and his team work together to aid you in this difficult time.

“The Sports Test-” Progress Report of Recovery

Dr. Anz’s team uses a ‘Sports Test’ to determine where an athlete is in the rehabilitation process. The test is usually scheduled at the eight- to nine-month mark, depending on the athlete’s goal for return to sport. The test evaluates strength through a mechanical test called a Biodex test, and coordination, proprioception and balance through functional movement screening and a y-balance test. There are many versions of this test, but their main goal is to objectively grade an athlete’s strength, coordination, proprioception, and functional movement patterns and, therefore, determine when they are physically equipped to return to sport. Again, there is no standard timeframe outlining when an athlete can return to competition. Therefore, Dr. Anz works with his medical team to evaluate each athlete and determine the goals they have met and the goals that still need to be accomplished. It is not uncommon for previously unknown deficits to be uncovered during a Sports Test. Through this identification, the athlete’s rehabilitation team can refocus and continue their efforts.

The Andrews SCORE: An Evidence-Based Multi-model Return to Sport Evaluation

At the Andrews Institute, a project is starting in 2022 to develop a data-driven decision making model to assess a competitive athlete’s readiness to return safely to sport after ACL injury and surgery. The model will include patient-reported outcome measures, objective and modern strength/ability testing, and MRI evaluation of healing tissues. The MRI evaluation will involve techniques already studied by the Andrews Institute and Auburn University.4 This return to sport algorithm will target competitive athletes with a return to sport that is congruent with their pre-injury level of play. The goal is to have a system to confirm that injured athletes are ready physically to return safely to their sport. This system will then allow for further study of biologics to expedite this return, proving readiness before return. The ligamentization process of the graft is always the wild card of knowing when athletes are ready for a full return.5 Our goal is to study if further and advance the biologic capabilities of ACL surgery.

It is critical to always keep the athlete’s best interests in mind, understanding the short-term gain and long-term health consequences of every decision.

As an Orthopedic Surgeon and Sports Medicine Specialist, Dr. Adam W. Anz is dedicated to providing individuals and athletes from all over the world with the highest possible quality of care. He serves his patients at the world-class Andrews Institute in Gulf Breeze, Florida. If you have sustained a sports-related injury, please contact our office today to schedule an initial consultation with Dr. Anz.

Sources:

- https://adamanzmd.com/acl-reconstruction/

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0363546514563282?journalCode=ajsb

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22922520/

- https://adamanzmd.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2019-3T-MRI-mapping-is-a-valid-in-vivo-method-of-quantitatively-evaluating-the-anterior-cruciate-ligament-rater-reliability-and-comparison-across-age.pdf

- https://adamanzmd.com/thebiologyofACLhealing-thewildcardofrecovery/